Divide between literature and understanding grows

Controversial books are often on and off the chopping block constantly in every state across the U.S.

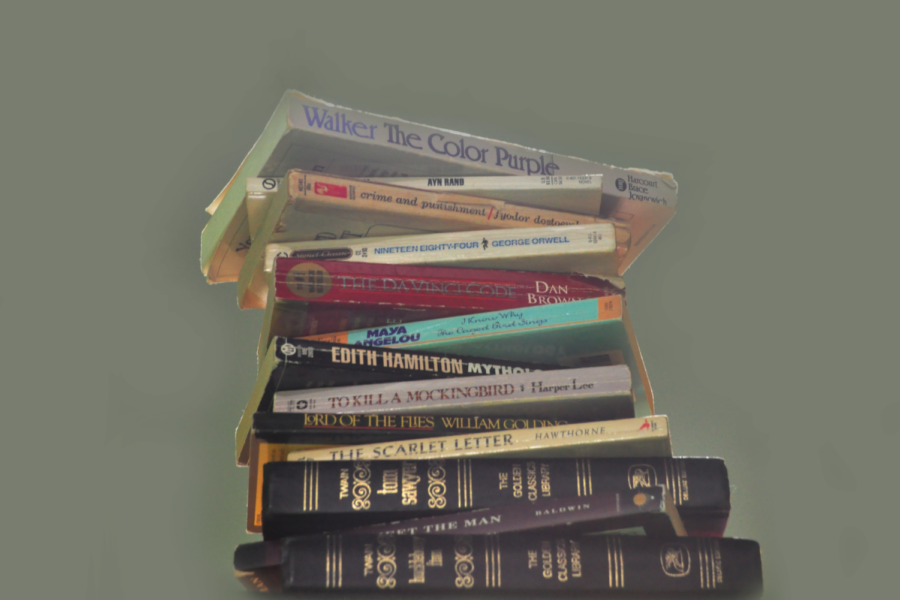

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Bridge to Terabithia. Captain Underpants. These are just a few of the most commonly banned books in America.

In the Chandler Unified School District, there is one group responsible for determining which books students in the district can and cannot read — a task that quite literally determines if and how children will be exposed to topics such as racism, rape, or mental illness.

“There’s a department called the IRC [Instructional Resource Center] and people that work in that department are the ones who approve books because really any book that’s assigned to students to read should be on the district-approved list,” Principal Dan Serrano said.

From the start of a student’s time at Perry, he or she is exposed to countless works of literature, all of which should be on the district-approved list.

“There are some [books] that are not [approved] and the district is trying to check that,” Serrano said.

Serrano has previous experience with controversial literature, as he became the principal at McClintock High School when the previous principal was removed during a 1998 lawsuit against the Tempe Unified High School District, with the plaintiff claiming the use of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the presence of racial slurs in the text led to racial harassment.

Such controversial works as Huck Finn spark debate time after time, even in the present at Hamilton High School.

Parents at Hamilton were outraged to find that their students were exposed to To Kill a Mockingbird and accompanying materials due to the author’s use of a racial slur over two hundred times.

One such parent is Ernest Russell, who told 12 News, “[The content is] just totally inappropriate for a 13-14-year-old audience.”

An article by Arizona State University professor Neal Lester — who teaches a class on the word — was used to discuss the word’s history, as well as its evolution into the present.

“As I get older and my students get younger, I find they are very disconnected with the realities of history,” Lester said.

As we move farther and farther from the past, literature that captures the essence of specific periods is one of the last remaining ways to keep history alive and accessible to future generations.

“History is history and I think that’s one of our jobs in an educational institution is to teach history, but some people don’t want us teaching history if it’s offensive to them so we work with them,” Serrano said. “There could be a book that you were forced to read that for your religion or your race or your culture or something that happened in history, it’s offensive to you.”

The complexity of the problem, though, is the fact that To Kill a Mockingbird and other commonly opposed books are indeed on the district’s list. While teachers safeguard themselves with permission slips and supplemental activities meant to effectively introduce controversial books, there is nothing anyone can do if the content of such literature offends a certain group.

“Now books have to be approved,” Serrano said. “If a kid still says, ‘I don’t want to read that book,’ we can’t make them read it. We have alternatives for students to read.”

The gray area comes with Dual Enrollment courses, as the college curriculum can include content that is not necessarily approved by the district, and may be more risque than the straight-laced content the IRC permits.

“Sometimes the books that aren’t on the list are Dual Enrollment books because you’re taking a college class,” Serrano said. “That’s kind of what we’re working on, because when you get to college I’m sure they’re a little bit different than ours.”

No matter how such literature is approached, it is perhaps unavoidable to present texts that no group will take offense to, as time and time again the question over the guidelines for educational exposure to such works is hotly debated.

I am a second-year opinions editor with experience in sports and features.