infographic by Sarah Lankford

Lack of education on sexual assault and harassment

Every 98 seconds someone experiences sexual assault, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. Out of only 47 anonymous students polled, eight claimed they were a victim of sexual assault or harassment on campus. However, only three cases have been reported school-wide this year. This begs the question: why is there such a gap between incidents occurring and incidents reported?

What it is:

The Department of Justice classifies sexual assault as any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient. This includes anyone touching, kissing, or making any unwanted contact with one’s body, forcing someone to pose for or look at sexually explicit materials, and penetration with a body part or object in the victim.

Sexual harassment is unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. This includes displays of pictures or other materials with sexually explicit content, rating a person’s sexuality, name-calling, and sexually suggestive sounds or gestures, among many other examples.

Committing sexual assault is a felony, and if convicted many perpetrators serve lengthy jail sentences, as well as coming out of jail on the registered sex-offender list. In Arizona, sexual assault is considered a class two felony, resulting in up to 14 years in prison if it is a first time offence and a date rape drug was not used.

When an event constituting as either sexual assault or sexual harassment happens to a student and is heard of by a faculty member, a process called “mandatory reporting” begins.

“Every year teachers have to go through a training that tells teachers ‘If you have any suspicion of harassment, bullying, hazing, abuse, you have to report it by law, because if you don’t you can get in trouble,’” principal Dan Serrano explained.

There is a system set up in the school through the counselors, nurse, and police officers. If a teacher or other faculty member become aware in any way of a situation happening, they must report it or risk facing from as low as a class one misdemeanor to a class six felony.

Mandatory reporting does not only cover situations that happen on campus, but also off campus as well. “If [faculty were to] hear about something, say I hear something happened on Saturday that’s maybe an abuse thing, I have to report it,” Serrano said.

What we found among students and teachers:

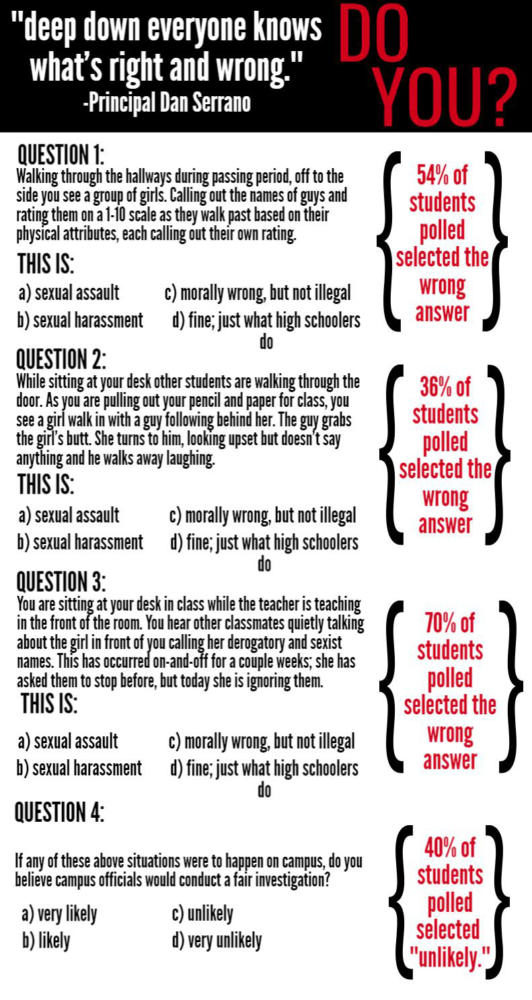

A simple explanation of what is actually considered sexual assault or harassment is unclear to students and faculty alike. In a poll distributed by Precedent staff, students and teachers were tested to see if they were able to identify sexual assault and harassment, as well as opinions on how the school would handle these situations and the preparedness of students.

When asked on the student poll asked if students felt they have been taught how to recognize and protect themselves from situations of sexual assault and/or harassment, in which 81 percent of students answered with “not really” or “absolutely not.” When teachers were asked if they believed students were accurately prepared to identify sexual assault or harassment and act on it, 82 percent answered with “unlikely” or “very unlikely.”

Without the knowledge of accurate definitions or procedures, students are left confused and unprepared when it comes to recognizing and handling sexual assault and harassment situations.

One student, Madeline Bishop*, has encountered two such situations on school grounds.

“I had been in my Spanish class doing a worksheet in a group, I was listening to music and doing the worksheet on my own,” she explained.

“I felt something hit my chest. I looked into my lap and saw a small piece of paper rolled up into the size of a pea. I groaned, and looked up. I saw a group of three guys in my class laughing, and trying to get paper down my shirt.

“I pulled my shirt up towards my neck and tried to keep working. I heard shuffling over the music, and looked up just in time to see one of them pull my shirt out and, holding a piece of paper, shoved their hand down my shirt. The guy said, ‘I told you I could make it, $5 dude.’”

At the Morp dance earlier this semester, Bishop experienced another assault scenario.

“I had been standing in the large group of people clustered, and dancing, and was facing my closest friends talking. A junior, who I barely knew, pushed his way through the crowd and forced himself into my friend group. He began to question all the girls in our group, two of us total, if we were ‘into grinding and stuff like that.’

“We quickly answered ‘no’ and kept continuing to divert his questions,” she continued. “As we were talking, he suddenly reached over from across the circle and grabbed my butt. I quickly swatted his hand away, relatively appalled, as he winked and moved on with his friends. Just like that, he moved on. Leaving me extremely uncomfortable, and honestly [furious] I didn’t do anything about it.”

The poll distributed contained a scenario similar to this, in which a student’s butt was grabbed in the classroom. Thirty-six percent of students polled and 18 percent of teachers polled were not able to identify this action as sexual assault.

Bishop did not go to any authority figures in response to either situation due to the fear of possibly being blamed herself.

“I just don’t really want to get police or administration involved because of stuff like ‘what were you wearing,’ ‘did you know them,’ ‘have you done stuff previously’ questions like that,” Bishop said. “I didn’t bother telling the teacher because A) the kids would probably just do it more [and] B) I’m not sure my teacher would do anything.

“Yes the guy still harasses me [as well as] two other girls that sit by me. The teacher either hasn’t noticed or doesn’t care.”

Bishop is not alone in thinking this way. The poll results show 42 percent of students believing it would be unlikely or very unlikely that administration would conduct a fair investigation of the situation. As well as 30 percent of students believing it would be unlikely or very unlikely that appropriate action would be taken against the offender.

What is taught:

The lack of information on what situations are classified as illegal ultimately trails back to the curriculum taught in health class.

Being the only place students are formally able to learn about sex education, the lessons – hosted by the North Star Youth Partnership organization, a program of Catholic charities – cover a range of topics related to sex.

Christy Leonard, the North Star Lead Health Education Supervisor, explained the topics covered and how they are delivered to students in the “Choosing the Best Journey” program that is taught by the organization at high school levels.

“When we go through it,” she said. “There’s an alcohol section that we talk about and there’s in the video where one of the girls talks about how she was sexually assaulted. We talk about that, what that means, that no means no, and which we go through that also on how to say no. That no matter how a person says no, no means no.”

Leonard commented that what precisely constitutes sexual assault and harassment is a difficult subject to properly teach.

“We tell them of course they can be arrested, that they could become registered sex offenders, they could spend many many years in prison…But we don’t get into too many specifics because there’s such a wide variety of sexual assault, anywhere from the misdemeanor of an adult exposes him or herself to another adult all the way to rape,” Leonard said.

Other than the North Star program, that presents a few scenarios and lessons for one week every year in health classes, there is not much more information offered to students in class.

Health teacher Louis Nightingale explained that since North Star is able to teach it, there is no need to cover much else related to it.

“It’s not in the curriculum. We talk about assault but not sexual assault,” Nightingale said. “I talk more about not putting yourself in situations. Keeping yourself out of parties where drugs are and putting yourself in one-on-ones and things like that. And that’s about sexual assault; it’s about not being in the situation.”

The North Star Youth Partnership staff that come in to teach health students are not certified teachers, but rather guest speakers. Because the health teachers, like Nightingale, stay in the room during presentations, North Star staff is not required to be certified.

Miscommunication regarding sexual assault and harassment has divided the student body and administration.

Without a clear idea of what defines assault and harassment, students are not able to notify the proper authority to receive any help to charge the perpetrator.

Without reports from students, administration is not able to properly maintain the safety of the student body. Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, has a hotline that can be called 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

*Name was changed at the request of the source.